Albert Low & Zen at War

On Suffering, Kensho, & Catholicism in Quebec

Introduction

If you're new here, or perhaps just tuning in, you might be curious about the name of my Substack: Integral Facticity. This platform officially launched as a space to explore a range of ideas, with a particular nod to my brother and Leonard Cohen—connections I hope will become clearer throughout this post.

When I first started my Substack, I wasn't entirely sold on using the same title as my podcast, Integral Facticity. While some early readers appreciated the continuity and its nod to the work of Michael Brooks and Matt McManus on postmodern conservatism, I personally felt it didn't quite encompass the full breadth of my philosophical, theological, and religious interests. Despite my initial reservations, I ultimately decided to keep the title. However, I added a personal touch with the subtitle, "Listen to the hummingbird, don't listen to me," a line from Leonard Cohen's song on his album, Thanks for the Dance. And with that, this site officially launched.

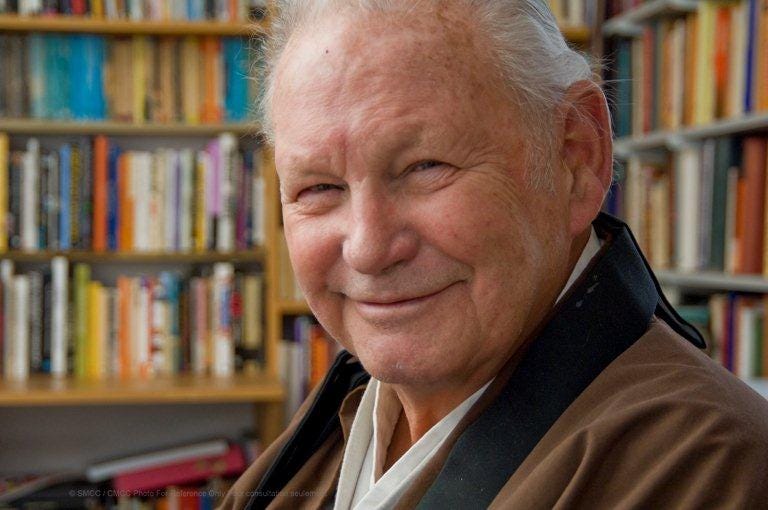

That said, this essay is a continuation of my previous post "Lament for a Nation - George Grant, Canadian Nationalism, & Religion in Canada," where I introduced my Zen teacher and first spiritual mentor, Albert Low. The inspiration for revisiting this topic stemmed from a public conversation between Cadell Last , Jim Palmer , and Brendan Graham Dempsey on the impact of deconstruction and reconstruction methods on traditional and modern forms of religion, and recently rereading Mauro Peressini's excellent biographical work on Albert. In this intimate and introspective exploration, I will delve deep into the multifaceted layers of my relationship with Albert. Our connection was a tapestry woven with threads of shared passions, intellectual pursuits, and deep mutual respect. Yet, it was also marked by stark contrasts in opinion and perspective, moments where our differing viewpoints created a dynamic tension. I will examine both these commonalities and divergences, illuminating how they shaped our interactions, challenged my assumptions, and ultimately fostered my own personal and intellectual growth.

Additionally, I will detail the transformative and tumultuous time I had at university, which irrevocably changed my spiritual and religious life. During this time, I embarked on a challenging and often disorienting process of religious deconstruction. As I grappled with critical scholarship on Buddhism and Catholicism, I found myself questioning and re-evaluating long-held beliefs that had once been the bedrock of my understanding. This exposure to rigorous academic analysis, coupled with personal introspection and existential questioning, led me to a profound reconfiguration of my faith and religious life. The once solid ground of my religious convictions shifted beneath my feet, forcing me to confront doubt, uncertainty, and the unsettling prospect of reconstructing my spiritual and religious identity.

Religious Background and Meeting Albert Low

My introduction to Buddhism came through my father, despite the fact that I had been baptized as a Catholic. Both my parents had horrible religious upbringings in Quebec and fraught with difficulties, leaving them with a complex and strained relationship with organized religion and the Catholic Church. While my father held strong, often critical views against the hypocrisy and historical wrongdoings of the Church, he paradoxically maintained a deep respect for the figure of Christ and the core tenets of his teachings. The tragic loss of my brother to leukemia marked a significant turning point in my father's spiritual and religious worldview. As he grappled with grief and sought solace, he found increasing comfort and resonance in the teachings and practices of Buddhism, Ken Wilber, and Leonard Cohen’s growing body of work at the time–and fell further and further away from Catholicism.

My father and I started having deeper conversations about life's meaning, philosophy, and religion during this difficult period. He introduced me to Ken Wilber's work and shared his growing insights and interests in Buddhism–and Zen in particular. This period would come to have a profound impact on my worldview and sense of self, as I have shared on my podcast with various guests and previous posts. It was at this point, the early 2000s, that I began studying at the Montreal Zen Center under the guidance of Albert. His teachings immediately resonated with me and complemented my own religious background. Albert's guidance marked the beginning of several profound spiritual experiences that deepened my connection to Zen and reconnected me to my Catholic roots through various mystics and the work of Thomas Merton. Interestingly, Albert himself never had anything good to say about the Catholic Church, though he continually drew upon various Catholic mystics in his teachings, talks, and writings.

Albert Low: Suffering and the Search for Truth

Before the official publication of Albert's biographical details, I was fortunate enough to be his student and learn directly from him. This early exposure provided me with unique insights into certain aspects of his life and story. However, to offer a more complete and well-rounded picture of his life, I have incorporated the meticulous research of Mauro Peressini to present a succinct biographical sketch of Albert.

Mauro Peressini's research on Albert began in 2005-2006 when he conducted filmed interviews with Albert for a research project on Canadian Buddhist practitioners. In 2007, Peressini met with Albert to discuss his chapter about Albert in the book "Wild Geese: Buddhism in Canada," which was published in 2010. Albert reviewed and updated the text of his life story for Peressini's work in "Choosing Buddhism" in February 2014. Reflecting on this, I wish I had access to all these details prior to studying with Albert. It might have helped me understand the complex dynamics within the community and the personal struggles Albert faced, including his family life and the challenges he encountered in his own spiritual development.

Revisiting Peressini's work now has provided me with a deeper understanding of Albert's life and teachings, shedding light on aspects that were not apparent to me during my time at the Montreal Zen Center. This renewed perspective has allowed me to appreciate the profound impact Albert had on my spiritual development and the broader context of his teachings.

Albert was born in 1928 in the impoverished Canning Town district of London, England. His early life was shaped by the Great Depression and World War II. Growing up in a poor family during these difficult times exposed him to the harsh realities of life. His father worked as a meter reader, and their family home was located in a gloomy industrial area. Albert's childhood and adolescence were characterized by a deep dissatisfaction with life as it presented itself to him. He always felt there had to be more, a sentiment partly due to the circumstances in which he grew up.

At the age of thirteen, during a walk in Cornwall, England, he had an intense experience of self-awareness, feeling "knowing was me." At seventeen, while lying in a park, he had another profound experience where he felt he was space and everything was made of space, with the trees, grass, and sky being of the same substance as him. These experiences contributed to his profound dissatisfaction, and ironically, hope.

In 1940, Albert experienced the bombing of London by the Germans from an underground shelter during the Second World War. In 1945, he was deeply marked by a documentary film on the horrors of Belsen, Buchenwald, and Auschwitz. These experiences, coupled with the post-war footage of concentration camps, led him to question the nature of life and human suffering.

In 1950, Albert met Doctor Nothman, a local general practitioner who was also a philosopher. This meeting was serendipitous, as Albert found an incomprehensible book, Alfred North Whitehead's "Adventures of Ideas," in the doctor's waiting room. Dr. Nothman invited him to join a reading and discussion group for young people interested in philosophy and psychology. This group discussed "Adventures of Ideas" and the works of Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, the founder of Dianetics, which later became Scientology. Albert found Hubbard's ideas a "fresh breeze" at the time. He experienced his first kenshō while reading Piotr Demianovich Ouspensky's "In Search of the Miraculous," where he encountered Gurdjieff's phrase "man does not remember himself," leading to a deep experience of self-remembrance that lasted several months.

In the early 1950s, Albert joined a small informal group in London that discussed Hubbard's ideas and invited his girlfriend, Jean, to join. In 1953, Albert and Jean married and, instead of a honeymoon, took the nine-month evening course offered by Hubbard. At the end of the training, Hubbard invited Albert to become a full-time lecturer at the Scientology center. By the mid-1950s, two students from South Africa persuaded Albert to accept a position as a Scientology teacher in Johannesburg.

Around June 1955, about fifteen months after arriving in South Africa, Albert wrote to Hubbard with twelve points needing clarification, but Hubbard dismissed his questions. Around this time, Albert happened upon Hubert Benoit's "The Supreme Doctrine," a book on Zen, which became a significant influence and a "second lifeline" after his break with Scientology.

In 1958, while living at a ranch in the Transvaal desert and studying philosophy and psychology through correspondence courses at the University of South Africa, immersed in Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason," Albert experienced a second kenshō upon encountering the notion of "noumenon." This was a profound experience of primordial unity. By the late 1950s, Albert climbed the professional ladder in South Africa, eventually reaching a senior level in an important company. However, he and Jean felt uneasy with the racial discrimination in South Africa. The Sharpeville massacre on March 21, 1960, and the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela in 1962 further contributed to their discomfort with the situation in South Africa.

In 1963, en route to Canada, Albert met Hubert Benoit in Paris and was deeply affected by his simplicity, strength, and openness. Albert and his family emigrated to Canada and eventually settled in Montreal. He initially worked various jobs before finding a position as a manager in the personnel department of the Union Gas Company. He continued to feel a deep dissatisfaction and a need for a new way of understanding. In March 1964, Albert began a regular meditation practice, sitting each morning before his children awoke, without formal training. He felt he was experiencing a "dark night of the soul."

By 1966, Albert began increasingly devoting himself to Zen Buddhism. He, along with his wife Jean and their friend Hilda, attended a weekend workshop led by the Japanese Zen teacher Hakuun Yasutani Roshi. This was his first encounter with a Zen teacher, and during this workshop, they learned basic meditation postures and breathing techniques and received their first koan, Mu. In 1967, Roshi Kapleau and Yasutani Roshi ended their relationship over teaching disagreements, and Kapleau became an independent teacher.

From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, Albert and Jean strived to attend as many sesshins as possible offered by Yasutani or Kapleau in Rochester or elsewhere. Albert experienced considerable "existential" suffering during this period, including dread, fear of death, anxiety attacks, and insomnia, which Kapleau identified as makyō. He found great support in books on spirituality, including works by Gurdjieff, Christian mystics like Saint John of the Cross ("The Dark Night of the Soul"), and poets like T.S. Eliot. They sometimes organized their own weekend retreats at home.

In December 1974, during a sesshin at the Rochester Zen Center (RZC), Albert attained his first awakening (kenshō) within the context of Zen practice. His account of this sesshin and awakening was later published in the RZC's Zen Bow magazine. He realized at the time of awakening that he received no new knowledge. Post-awakening, Albert continued his training with Kapleau for another twelve years, working on the koan collections Mumonkan and Hekigan-roku. He began to apply his understanding of Zen to his work, leading to the publication of his article "The Systematics of a Business Organization."

In 1976, his article was expanded into the book "Zen and Creative Management," which was published and became successful. Due to opposition to his book from senior management and a less receptive new president at Union Gas, Albert lost interest in his job. He and Jean began planning their departure and a new phase in their lives, motivated by his awakening and desire to share what he had received.

In 1979, Albert and Jean moved to the Rochester Zen Center for three years of residency. Albert also accepted the position of leader of the Montreal Zen Group, which Kapleau had founded in 1975. They faced difficulties adjusting to community life and being supervised by younger individuals. Albert became the editor of the center's magazine, Zen Bow. His relationship with Kapleau began to deteriorate due to disagreements about Zen practice. By the early 1980s, Albert began leading more meditation sessions in Montreal, eventually leading three-day sittings. Around 1983, Albert and Jean left the Rochester Zen Center and returned to Montreal.

The Montreal Zen Center (MZC) became fully independent in 1986, when Albert received full transmission from Philip Kapleau. As the MZC's director and spiritual director, Albert established a rigorous annual schedule, which included thirteen six-day sesshins, beginner's workshops, and workshops in other locations. Albert was also a prolific author who connected Zen and Western thought and spirituality in his writings. His notable works include:

Albert passed away on January 27, 2016, leaving behind a legacy of dedication to Zen practice and teaching. His life reflects a deep engagement with the principles and practices of Zen Buddhism, emphasizing the importance of direct experience, meditation, and the integration of Zen principles into daily life.

Leonard Cohen, Ken Wilber, & Zen at War

My early connection with Albert Low was immediate and powerful, forged by similar family and childhood experiences, which I was reminded of by Mauro Peressini's work. But it was our shared admiration for Leonard Cohen that cemented our bond. Through countless conversations and discussions on Leonard Cohen, we found solace and understanding in each other's company, a connection that resonated deeply and shared many similarities with my relationship with my father.

As our friendship grew, my spiritual practice deepened tremendously. Albert's wisdom and insight were invaluable, leading me to my own kensho experiences. However, these profound and transformative experiences weren't entirely new to me. Even as a child, I had similar flashes of insight during moments of deep connection with nature, like the beauty of a sunset or the serenity of a forest. These experiences always felt sacred, but I didn't have the context to fully grasp their significance.

Later, as a young athlete, I found that intense physical exertion could also trigger kensho-like moments. During intense training or competition, I would sometimes enter a flow state where my mind and body were in perfect sync, and the world around me disappeared. In those moments, I felt a oneness with the universe that transcended my physical self.

My early experiences were foundational in establishing my connection with Albert, a relationship that profoundly expanded my awareness and comprehension of a reality that transcended the mundane and everyday. Through his guidance and mentorship, I was able to nurture this heightened awareness and progressively integrate those ephemeral moments of enlightenment into the fabric of my daily existence, thereby enriching and deepening my spiritual life.

Although Albert and I were close, he had significant reservations about my exploration of Ken Wilber's teachings, arising from a personal issue with Wilber that he never explained. Furthermore, his persistent questions about my livelihood led me to follow his career path in business and return to university to pursue my interests in psychology, philosophy, and religion. Ironically, this decision, initially made to appease Albert, eventually led me to develop a critical perspective on both Wilber and Albert.

My academic journey at Concordia University proved to be a pivotal turning point. It was there that I encountered Brian Daizen Victoria's "Zen at War" and Robert H. Sharf's insightful analyses of the Sanbo Kyodan lineage and Hakuun Yasutani, who first introduced Albert to Zen practice. These works served as a catalyst, deconstructing the idealized image I had held of Albert and compelling me to re-evaluate his role as my spiritual mentor. The unquestioning reverence with which I had regarded him began to wane as I grappled with the complexities and contradictions revealed by these scholarly works.

Sanbo Kyodan and Modern Buddhism

The revelations in "Zen at War" about Yasutani Hakuun's support for Japanese militarism during World War II were particularly troubling. Yasutani's nationalistic views and his involvement with Japanese militarism cast a shadow over the Zen lineage that Albert was a part of. This historical context forced me to confront the uncomfortable reality that the Zen tradition I had revered was not immune to the moral failings and political entanglements that I had hoped it transcended.

Albert's own teachings and practices were deeply influenced by Yasutani, and this connection now appeared in a more complex and problematic light. The idealized image I had of Albert as a purely spiritual guide was challenged by the realization that his lineage carried the weight of historical and ideological baggage. This awareness led me to question the extent to which Albert's teachings were shaped by these influences and how they might have impacted his approach to Zen and his interactions with students.

Robert H. Sharf's analyses of the Sanbo Kyodan lineage further complicated my understanding of Albert's background. The Sanbo Kyodan, founded by Yasutani Hakuun, emphasized kensho and the use of koans, diverging from more traditional models found in Soto, Rinzai, or Obaku training halls. This modern and somewhat controversial approach to Zen practice, which Albert had adopted, now seemed less like a pure spiritual path and more like a product of its time, influenced by the socio-political context of post-war Japan.

The Sanbo Kyodan's emphasis on kensho and the rapid advancement through the koan curriculum, often at the expense of traditional monastic training and ritual, raised questions about the depth and authenticity of the spiritual experiences it promoted. This realization made me more critical of the methods and practices that Albert had inherited and passed on to his students, including myself.

The insights gained from "Zen at War" and Sharf's analyses led me to a more nuanced and critical understanding of Albert. While I continued to value the profound spiritual experiences and insights I had gained under his guidance, I could no longer view him through the same lens of unquestioning reverence. The complexities and contradictions in his life and teachings, as well as the historical and ideological context of his Zen lineage, became an integral part of my understanding of him

Conclusion

My journey through Zen Buddhism and my relationship with Albert have been nothing short of transformative, yet they have also been fraught with complexity and challenges. Initially, I held an idealized view of Zen and its historical narrative. However, as I delved deeper into scholarly research and critical analysis, I uncovered troubling aspects of Zen's history, which led to a more nuanced and, at times, disillusioning perspective on both Zen as a tradition and Albert as a teacher. Despite the disillusionment, my personal experiences of kensho remain unshakeable pillars in my spiritual life, standing as testament to the transformative potential that Zen undoubtedly holds.

Parallel to my Zen journey, my understanding of Catholicism has also undergone a profound evolution. I moved from a rigid, dogmatic framework to a nuanced, open-minded perspective, fostered by intellectual inquiry and spiritual exploration. This shift allowed me to reconcile faith and reason, integrating my spiritual beliefs with critical thinking and intellectual honesty. It was no longer about blind acceptance but about informed faith in-action.

Through these diverse experiences, encompassing both Eastern and Western spiritual traditions, and through the challenges they presented, I have come to deeply appreciate the importance of critical examination and intellectual rigor, even in the realm of spirituality and leading a deeply religious life. This ongoing questioning and self-reflection, far from undermining my faith, has enriched my understanding of the world and my place within it. It has allowed me to navigate life's complexities with greater wisdom, compassion, and discernment.

True spirituality and religious life are not about blind faith and unquestioning obedience. They are about engaging with the complexities of the world, grappling with difficult questions, and seeking truth and understanding. It is about accepting paradoxes, embracing uncertainty, and acknowledging that the spiritual path is not always straightforward.

My spiritual journey has been an ongoing process of learning, unlearning, and relearning. It has been about letting go of illusions, facing uncomfortable truths, and moving toward a more authentic and integrated way of being. The journey I've shared with Albert has been far from easy; it has been fraught with obstacles that pushed me to my limits, forcing me to confront my weaknesses and question my assumptions. Yet, amidst these trials, there have been moments of profound clarity, where my understanding has been illuminated, and my perspective has been irrevocably altered.

I am eternally grateful for these experiences; they have been both challenging and enlightening, and have shaped my personal development and life into what they are today. The bond that Albert and I have forged through these shared experiences is what I cherish the most. Our relationship, which has been tempered by adversity and illuminated by moments of divine revelation, holds a special place in my heart, and for that, I am truly thankful.

![Integral [+] Facticity](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!yhcJ!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff8458843-3278-4fcc-accc-17ad21352205_1280x1280.png)